Our learning environment, the tools we use in work with, the complexity of the activity and the distractions seated next to us all influence our capacity to engage and understand the task at hand. The more distraction, the more significant the erroneous information, the less capable we are of seeking a solution to the challenge we’re faced with.

While our long term memory is effectively limitless, our working memory can only hold so much at any one time. We are also further challenged in our efforts with the awareness that new information takes up more working memory that familiar information.

The limited resource that is student memory is something teachers strive to protect and employ to best advantage in their classrooms, but the balance of determining the best approach can be complex. Judging the right amount of information that students can accommodate in working memory, and the need to relate new information to prior knowledge to help it transition to long term memory is tricky.

In any classroom activity we must strive to ensure that we reduce the extraneous load and optimise intrinsic load. We must take care in the way we introduce new challenges, balancing chunked new information it with the familiar, and ensuring that we have enough scaffolded prior knowledge drawn from long term memory at play to support development of new ideas.

As Lovell observes (Lovell, 2020) on Swellers work ‘For any learning to take place, a number of elements of new information must be considered and related in working memory, and then incorporated into long-term memory. The more elements of new information that a student is required to think about – to process in their working memory – during a learning task, and the more complex the relations between these elements – the number of interactions – the more challenging the learning task will be.’

How then do we reduce extraneous information while providing students with the best advantage by leaning in on what they already know?

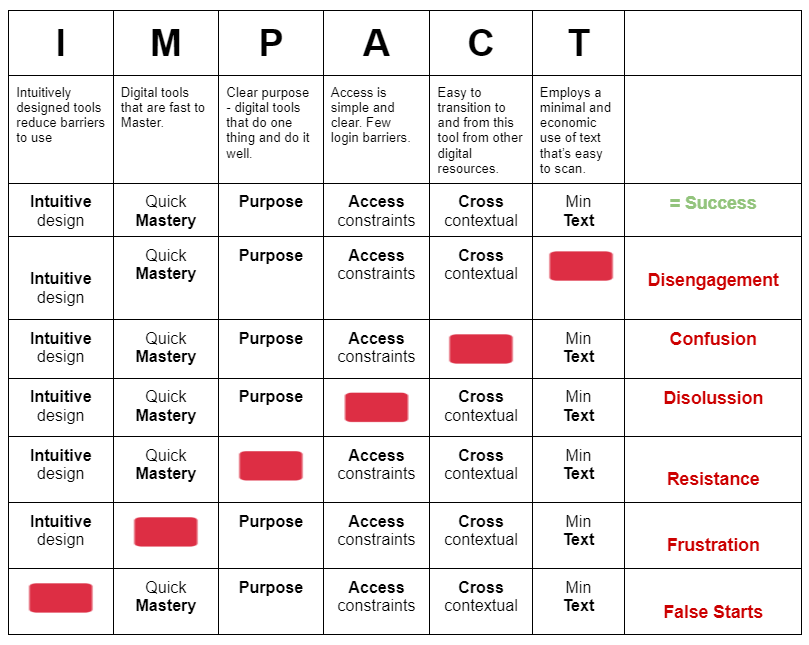

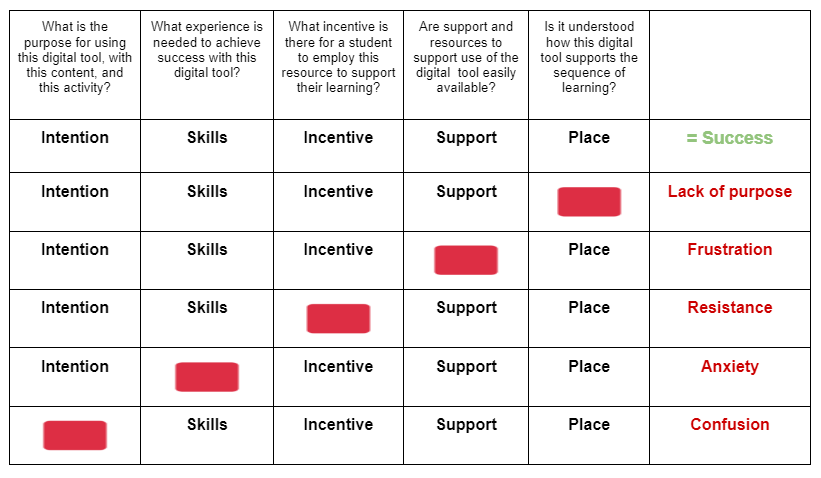

The checklist below has been designed to help you achieve the right balance in your planning and delivery. Before we begin though, a few quick definitions to ensure clarity.

Intrinsic cognitive load is the complexity of new information. It’s the amount of cognitive resources you need to shift new information from your working memory, to long term memory.

Extraneous cognitive load is the way information or tasks are presented to the learner. Extraneous load is used describe the distractions that prevent our working memory from processing new information. This is the stuff that get’s in the way of shifting new information into long term memory.

Germane cognitive load refers to the effort put into creating new and permanent knowledge (a schema). This is the deep processing of new information, placing new ideas into long term memory and integrating that new information with previous things we’ve learnt.

In other words, we need to manage our intrinsic load and reduce our extraneous load in order to maximize our germane load. Or to put it another way, we need to focus on only what’s relevant, removing any distractions to ensure a transfer to long term memory.

First, let’s determine whether the learning sequence includes unnecessary extraneous load:

o Split attention: Students are not forced to divide their attention between sources of information that are separated? For example, ensuring labels on a picture are closely related in the diagram, or information needed for the problem is not split across several pages.

o Reduced redundancy - all irrelevant information has been reduced or removed that may cause extraneous cognitive load. This may include the duplication of information in a presentation for example.

o Redundancy duplication – Ensure images and text do not present the same information.

o Expertise reversal – What is redundant to an expert is not redundant to a beginner. As students gain skills, they need supports like worked examples reduced or removed to support their increased capacity. This process of reducing the explicit guidance used with students as they progress from novice to greater levels of expertise is called the ‘guidance fading effect.’ (Sweller, 1981).

o Transient information - is the information needed to resolve a present challenge easily accessible? Has it only been verbally explained, or is there another easily available reference point in a contextually relevant spot for the student such as a brief and pointed playable audio file? A summary of steps you’ve outlined or a graphic that represents key concepts that relate to the next immediate activity are also ways you can resolve this one.

Now, let’s consider the design of your learning sequence:

Relatedness - Are any parts of the task unrelated to the problem at hand? For example, have you included in your instructions the broader goals of the project that don’t add context for the immediate problem. Grammar and structure are important considerations, but perhaps they don’t have to be while the student is engaged with an immediate problem and could be reflected upon after the fact. Once you start looking, you may find all sorts of information you’d included that can be removed without impacting upon the capacity of the student to respond.

Goal free effect - Is the student given the purpose of pursuing an obvious goal (eg the ‘right answer’)? Too great a focus on goals can help students complete the task, but reduce their level of understanding of the problem. It seems counter intuitive, but the more focus you can place on solving a problem, rather than reaching a predetermined goal, the more capacity the student will have to respond to that problem.

Modify the task to ensure the student’s focus remains on the mechanics of how to solve the problem, ‘…a focus upon getting the right answer drives both attention, and cognitive resources, away from the actual process of learning.’ (Sweller, 1981).

Divide the task - Has the task been broken down into component parts (often called chunks) sufficiently that the student will not be overloaded by too high an intrinsic load? Present all 6 courses of the meal at once and you’ll overwhelm, instead provide it in accessible portions that don’t individually overwhelm to ensure a focus on only what is immediately relevant..

Preparatory knowledge – What do the students’ need in advance of the task? Consider pre-teaching key concepts to reduce the cognitive load. For example, you might introduce the characters before a play or a discussion of an historic event to avoid students becoming overloaded with too much information.

Exposure - Have you considered timed exposures to the content? Graham Nuthall’s (Nuthall, 2007),) work recognises that students require on average three exposures to a new concept to understand it. Perhaps try employing an approach that provides for germane load by spacing the learning over time (Pashler et al., 2007) or varying practice (Soderstrom and Bjork, 2015).

Contextual Interference – This is the impact of moving between problems with different skills required to address each one. Low contextual inference is achieved by solving problems using the same tools. Students that practice in high contextual interference environments become more skilled at moving between them over time, but take longer to acquire new skills (de Crook, 1998 ). Consider how much variation there is between the types of tasks you’re challenging students with, consider the order in which you’re presenting them and where scaffolding may support more than one in the sequence.

Words and pictures – Where possible, support understanding by drawing on both types of working memory: language processing (written or spoken) and visual processing (images) that provide different but relevant and related information? This ‘dual coding’ strongly reinforces retention.

Worked examples – Carrying a high effect rating, ensure that the presentation of a worked example is brief and targeted and followed immediately by student practice. Long presentations (over 6 mins) overload working memory and if they are followed by lengthy problem solving, are far less likely to be an effective. Maintain a clear link to an immediate goal, increasing motivation and reducing the likelihood of misconceptions arising (Sweller, 2011).

Self-explanations – Ensure you include opportunities for students to reflect on the principles or value of the approach – this is a powerful way to embed the experience of a process to long term memory. Ensure the reflection is pinned to previous problem attempts helps students relate current work to previous efforts and then to new problems.

Use process prompts – A powerful way to guide elf-explanations, these can be used as metacognitive triggers to help students understand and more readily apply patterns or solutions to new problems they encounter (Rittle-Johnson, 2017).

The nuances of cognitive load and their impact upon the capacity of any student in your classroom are considerable. Armed with a keen sense of the key considerations under this theory, your students will have a far greater capacity to pursue the challenges that lie before them.

However, while we may plan for optimum learning experiences, many students come our classrooms hindered by circumstance. Our current reality, the reality for many young people, is that trauma plays an impactful role on their capacity to learn in our classrooms. Trauma hinders working memory still further, affects motivation, cognition, engagement, retention and participation (Bangasser and Shors, 2010). Stressful experiences can notably alter brain circuitry, impacting particularly on our capacity for learned associations.

While therefore a strong awareness of cognitive load and its impact on learning can make a notable difference in designing experiences that are more accessible, knowing your students and deeply understanding their needs is just as crucial. Being acutely aware of their readiness to learn is undoubtedly an equally important consideration as you seek success with them.

Want to look further at Sweller’s theory? I’ve found that Oliver Lovell’s work on Sweller is not only accessible and relatable, but a very enjoyable read!